Can’t recall

when was the last time I blogged here. 2010? 2011? If I was to write a piece on

music industry then, the view would be gloomy. Something like “the industry is

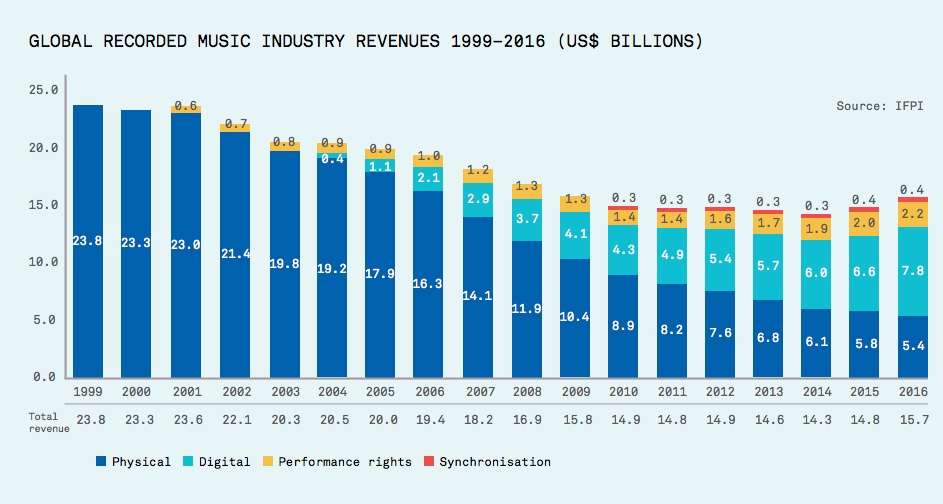

dying”, “digital piracy is killing music”. Just look at this graph (credit to IFPI) :

The industry’s

total revenue experienced a free-fall since 2000 – right, the MP3, Napster,

peer sharing, piracy fiasco we heard back then. The free-fall stopped around

2010. It hasn’t been bouncing back, but the bottom may have been reached.

Remember that in 1980 The Buggles said video killed the radio stars? In fact, 1980 was just a beginning of the golden era of music industry. (And it was video – VHS and Betamax – who disappeared, not radio). So perhaps today we see another turning point, not a decline, in the industry.

Remember that in 1980 The Buggles said video killed the radio stars? In fact, 1980 was just a beginning of the golden era of music industry. (And it was video – VHS and Betamax – who disappeared, not radio). So perhaps today we see another turning point, not a decline, in the industry.

Streaming and the importance of sunk cost

Looking

closer at the data, it’s clear that digital music, which caused the decline at

first, has given the industry a lifeline. Digital music came in various forms:

paid downloads (like iTunes), subscription service (Apple Music, premium Spotify),

or on-demand streaming (YouTube, free Spotify). In 2015, the combination of all

digital music overtook revenue from physical sale (which has been helped by a

curious come back of vinyl records). In addition, revenue also comes from live

performances and royalties from movie or game soundtracks (which helps Led Zeppelin or AC/DC enjoy a brief popularity among teenagers).

Of digital

music, paid download was popular until a couple years ago. But streaming has increased, and now

makes up more than half of digital music revenue in the US. Technology explains part of

this – thanks to better internet connection and compression technology, streaming

is much better today.

Pricing is

another. Subscription price means I only need to care about my fixed cost (or,

sunk cost), not the marginal one. This

is a new way of enjoying music. Back then, when I want to own Skid Row’s first

album, I paid Rp5000 (guess what year was that) for 10 songs, of which I liked

only 4 or 5. Then I need to think, should I pay another Rp5000 for Debbie

Gibson’s Electric Youth, in which I only enjoy 2 songs. What if I don’t like

the albums after all? What if I get bored after a month? Subscription service

made my life easier. I only need to

think of paying once a month to have a huge range of options of music I want to

listen to, or don’t want to.

Like gym

membership years back, looks like subscription-based pricing will be our new

norms for many things. It means our decision will be driven more by sunk costs

rather than marginal costs. (Free streaming service is basically the same,

unless someone pays our bill in the form of ads).

Complicated royalty scheme

For artists,

things look a bit more complicated. In the old days, for every $18 wepurchased on a CD, around $10 went to labels (for their marketing, production, distribution,

and profits), $5 for retailers (most of them are now out of business), $3 for

the artist, and $1 for the songwriter. Yes, if you’re an artist-writer, then

you got $4. You got the revenue when I the CD, and not need to bother when will

I actually listen to your song and for how many times.

It’s similar

under paid download scheme. If I download Adele’s single from iTunes for $1.29,

I paid Apple 30 cents, and Sony 90 cents. Sony will then pay 8 cents in songwriting

royalty to Adele and her co-author. Adele will get another payment from Sony an

artist, depends on whatever mentioned in the contract, which ranges around

12-20 percent of sales.

Streaming

service is much less straight forward. Every time I listen to a song, artist

will get something. But it depends on certain algorithm like artist rate,

region, streaming time (prime or non-prime time). For one stream, an average song

generates $0.005 to $0.008, which will be split between the artist, songwriter,

and the label/management. An indie band revealed, after their songs were

streamed for 1 million times, their payment was less than $5000. Just

calculate how many streams it takes for Beyonce who earned $1.9 million from streaming in 2016.

Live performance makes artists still alive

One thing is

still a puzzle for me. According to an industry report, digital music accounted

for 50% revenue in 2016, while performance rights (including live shows)

accounted for 14%. But for top artists, streaming is only a small fraction of

their earnings stream. Top earners got 90% or more from performing live. Even physical

sales still generated more than streaming.

So who

earned from streaming?

My

hypothesis: digital music helps many non-major, independent musicians to sell

their pieces. Top artists still dominate all revenue sources, for sure. But the

digital space is so huge with fewer middlemen, so smaller artists can be part

of the game. There was only small space in Aquarius Mahakam and Duta Suara for

non-label artists, think about the old days. In a way, this may be a good

thing.

Live shows

have also been the way for old artists to stay in the game. Last year’s topearner may be Beyonce. But guess who others on the list? Guns N’ Roses and

Bruce Springsteen. They may not catch up with newer artists in terms of

streaming and record sales, but their revenue from live performances lifted

them to the second and third place. Similarly in 2015, The Rolling Stones,

Billy Joel and Grateful Dead were side-by-side with One Direction and Taylor

Swift in the top earner list, thanks to their live concerts.

So what’s next?

We are still

in the middle of disruption process, so hard to draw the conclusion for now.

Streaming, like smartphone is today, but may not be tomorrow’s game.

Music may be

surviving in terms of sales and revenue. But is the quality improving? Some are

complaining that today’s pop music has less variation (meaning they all sound alike), indicating lower creativity. Yeah, maybe no one wants to be Genesis anymore,

producing 30-minute tracks.

The role oflabels, and today’s marketing channels are other questions for next articles (maybe). And of course, understanding the Indonesian context. For now, it’s too much already for an economist of jaman old trying to

understand jaman now.

No comments:

Post a Comment