In my Facebook note, which have somewhat become the substitute for blogging, we have a productive exchange on, again, market. Specifically, on why most economists believe in the market, what are the limits of the market, and how the economics as a discipline has evolved and integrated the so-called 'non-mainstream' approaches. One of the 'non-mainstream' approaches is the field of behavioral and experimental economics. Basically, they show how the rationality assumption is often violated due to cognitive, emotional, bounded rationality etc.

I just recalled some readings by Harvard's Sendhil Mulianathan that addressed how psychology and behavioral perspectives can help us understand more why rationality assumption often fails, particularly in the context of poverty: this one, this one (with Richard Thaler), and this one (with Marianne Bertand and Eldar Shafir). Those three are basically emphasizing each other. He discussed some cases in which the rational maximization model may not be a very good approximation of human behavior, especially when we talk about poverty: underinvestment in education, undersaving, loss aversion in property rights assignment, misaligned teacher's motivation or low take-out rate of social programs.

I admit that, yes, we have to keep rethinking our epistemological position on rationality and how the market works and doesn't. On the other hand, we as economists do know that market often fails, hence it results in suboptimal outcome. But what we doesn't always know why it fails, let alone what solution should we prescribe. The reason is because "all working markets are alike, every failed markets fails in their own way." Meaning, we need to see things case by case and come up with specific - take a deep breath - policy implication, if any.

So why do we still stick to our mainstream or traditional economic tools? Because it is still a good tool. It enables us to: 1) compare the outcomes when the market works (called the benchmark condition) with the one under market failure, 2) analyze which assumptions are violated, 3) think about what - take a deep breath - policy implication, if any.

Showing posts with label Market Failure. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Market Failure. Show all posts

Friday, October 16, 2009

Wednesday, July 02, 2008

Down with the Bear

If you have a long commuting trip, are stuck in a traffic jam, or don't know what to do to spend the weekend, I suggest you to pick up the latest Vanity Fair. No, not the Nabokovesque Miley Cyrus' (a.k.a Hannah Montana) photo shoot --that's in the past edition--, but this 8 pages long in the website version, or 16 full pages if you print it, journalist's investigation on the last days of the once mighty Bear Stearns.

It tells you how those big names in the financial world work, how influential the media is (CNBC, to be specific), and how the nervous Fed acted. If you don't know the different perceived style between Lynch, Sachs, Stanley, and Stearns in making money, like I do; or how important to speak up to the right news anchor is; or how close the Fed, Treasury, and Wallstreet are; then, perhaps, it's the right reading.

Here is what happened in that fateful night of the Bear.

A caveat, it's a journalist report, so don't expect for a heavy bibliography. Whether the account is true, let's wait for the responses from the parties mentioned.

It tells you how those big names in the financial world work, how influential the media is (CNBC, to be specific), and how the nervous Fed acted. If you don't know the different perceived style between Lynch, Sachs, Stanley, and Stearns in making money, like I do; or how important to speak up to the right news anchor is; or how close the Fed, Treasury, and Wallstreet are; then, perhaps, it's the right reading.

Here is what happened in that fateful night of the Bear.

That day was Dimon’s 52nd birthday, and he was celebrating with a quiet family dinner at Avra, a Greek restaurant on East 48th Street. He was irked when his private cell phone rang; it was to be used only in emergencies. On the line was Parr, who put Schwartz on as Dimon stepped outside onto the sidewalk. Schwartz quickly explained the depth of Bear’s plight and said, “We really need help.” Still irked, Dimon said, “How much?”In case you don't know the names: Jamie Dimon is the JP Morgan's CEO, Gary Parr a top investment banker of the Lazard Freres, Alan Schwartz the Bear Stearns' CEO, Tim Geithner the New York Fed's President.

“As much as 30 billion,” Schwartz said.

“Alan, I can’t do that,” Dimon said. “It’s too much.”

“Well, could you guys buy us overnight?”

“I can’t—that’s impossible,” Dimon replied. “There’s no time to do the homework. We don’t know the issues. I’ve got a board.”

The people he should call, Dimon said, were at the Fed and the Treasury—the only place Bear could get $30 billion overnight. Still, Dimon promised to see what he could do to help. He hung up and dialed Tim Geithner at the New York Fed downtown. Twenty-first-century Wall Street is a highly interconnected world, with just about everyone lending billions of dollars to everyone else, and Geithner worried that Bear’s collapse might trigger a domino effect, taking down scores of other firms around the world; he urged Dimon in the strongest terms to think about somehow helping Bear. “Tim, look, we can’t do it alone,” Dimon said. “Just do something to get them to the weekend. Then you’ll have some time.”

A caveat, it's a journalist report, so don't expect for a heavy bibliography. Whether the account is true, let's wait for the responses from the parties mentioned.

Monday, January 28, 2008

Blame it on the liberalization?

Following the recent soy bean and other food commodities price hike, some people blamed globalization and liberalization of agriculture market as the main culprit. This is the logic (the abridged version): low import tariff drove down domestic prices so local farmers had little incentives to produce more. This creates high dependency on imports, which is bad because we are very vulnerable to global price fluctuations, like what we are experiencing now.

If we are talking about soy bean, then this kind of argument is fallacious. We have been a net importer of soybean since mid ‘70s. Long before the agriculture sector is liberalized. In other words, we have been dependent on imports since long ago. The second line of argument said that if we protect our farmers, at least our domestic production could have been higher so we can have a buffer stock as a cushion against global price fluctuation.

Actually, that can be true only if we are a big enough player in the global market. If we are a small player, like the case of soybean, then at best buffer stock can only ensure that domestic prices do not exceed global prices. But the overall trend of price increase may not be altered.

Now move to the food commodity in general. The fact is straight: the productivity of our agriculture sector is lower than that in the ’80-90s. Again, the question is whether liberalization of agriculture sector to blame. Let’s say that liberalization has got something to do with that. Nevertheless, these other factors have also affected productivity, and they have nothing (or less) to do with liberalization:

If we are talking about soy bean, then this kind of argument is fallacious. We have been a net importer of soybean since mid ‘70s. Long before the agriculture sector is liberalized. In other words, we have been dependent on imports since long ago. The second line of argument said that if we protect our farmers, at least our domestic production could have been higher so we can have a buffer stock as a cushion against global price fluctuation.

Actually, that can be true only if we are a big enough player in the global market. If we are a small player, like the case of soybean, then at best buffer stock can only ensure that domestic prices do not exceed global prices. But the overall trend of price increase may not be altered.

Now move to the food commodity in general. The fact is straight: the productivity of our agriculture sector is lower than that in the ’80-90s. Again, the question is whether liberalization of agriculture sector to blame. Let’s say that liberalization has got something to do with that. Nevertheless, these other factors have also affected productivity, and they have nothing (or less) to do with liberalization:

- Public investment in irrigation infrastructure is inadequate and has been declining. It needs about a third of the current central government budget to improve the irrigation infrastructure just to return to the mid-90s level.

- Investment in roads, especially rural roads, has also been declining. In 1994, public expenditure by all levels of government was 1.4% of GDP. In 2002 it was less than 1%. More than 40% of roads are in damaged or severely damaged conditions. Without proper roads available, it is difficult for rural farmers to reach the market it nearby towns.

- Real expenditure on agriculture research is only 0.1% of GDP (Bangladesh spends 1% of its GDP), and it is less than that in 1995. That explains the lack of invention in new, more productive crops or farming techniques.

- Only around 20% of land plots are certified. This explains the lack of access to credits that is still a problem among poor farmers.

- Domestic market failures resulting from imperfect or asymmetric information, bureaucracy, distribution chain etc. that creates a significant gap between the price consumers pay and farmers’ revenue.

Friday, April 06, 2007

Market? What market?

There are those who completely in denial of market existence and there are those who dismiss any non-market solution. Even the most ardent supporters of market sometimes slip: they think market is so powerful you don't need to do anything. On the other extreme, the market deniers think people are all too stupid, there is a call for government in virtually everything.

We are not in either group. (Despite the accusation that we are free market diehards).

Letting a problem in the hand of market has its own cost. If that cost is greater than the cost of managing it under a controlling command, you want an organization. Or, in business lexicon: firm. In a firm you have a manager who assign you and others, tasks. Think about a small firm with one manager and three workers. It is less likely that the manager knows all of you too well, she pays each of you wage exactly worth your contribution to the firm. Furthermore, it is less likely that he knows you perfectly, that he can assign you a work that really exploit all your potential to the limit (and pay you accordingly). Why not and not? Because the cost of getting the right information for those questions is too much.

Yet, firm exists. It should then be true that the cost of letting the market handle it (the matching of your pay and your do and your being) is even higher. Just imagine you go around telling everybody on the street that you can do this and that. And somebody else goes around asking people if one happens to match exactly what she needs to work for her. And imagine this is not just you and her. But everybody, all people. Why this is not happening? Because it's too expensive.

So it leaves us with firm or market. Or more accurately: a particular firm, other firms, and the market. If the particular firm happens to be able to manage things most efficiently (that is, with the least cost), then it will prevail. The others, gone.

You should now understand why some firms are big, some small. Or, why that thing called government still exists today.

We are not in either group. (Despite the accusation that we are free market diehards).

Letting a problem in the hand of market has its own cost. If that cost is greater than the cost of managing it under a controlling command, you want an organization. Or, in business lexicon: firm. In a firm you have a manager who assign you and others, tasks. Think about a small firm with one manager and three workers. It is less likely that the manager knows all of you too well, she pays each of you wage exactly worth your contribution to the firm. Furthermore, it is less likely that he knows you perfectly, that he can assign you a work that really exploit all your potential to the limit (and pay you accordingly). Why not and not? Because the cost of getting the right information for those questions is too much.

Yet, firm exists. It should then be true that the cost of letting the market handle it (the matching of your pay and your do and your being) is even higher. Just imagine you go around telling everybody on the street that you can do this and that. And somebody else goes around asking people if one happens to match exactly what she needs to work for her. And imagine this is not just you and her. But everybody, all people. Why this is not happening? Because it's too expensive.

So it leaves us with firm or market. Or more accurately: a particular firm, other firms, and the market. If the particular firm happens to be able to manage things most efficiently (that is, with the least cost), then it will prevail. The others, gone.

You should now understand why some firms are big, some small. Or, why that thing called government still exists today.

Tuesday, February 20, 2007

Market Failure: Fake Scientist and Her Wild Pink Yam Pills

A frequent visitor of this cafe once told me that he's amazed with economist abhorrence toward banning or regulation. Well not always. The standard text-book told us that government regulation might be needed if competitive market fails to prevail. And one among reasons why market does not work efficiently is the problem of incomplete (asymmetric) information.

And this is the hilarious yet tragic example of it: the fiasco of self-proclaimed scientist turned TV celebrity and best-selling author in UK. Here is the lead:

To prevent that thing happens and to rectify the market efficiency, economics allows various government related authorities to step in --Advertising Standards Authority and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, in this case.

You see, mate. We don't always hate government and loathe regulation.

ps: Following Aco, I was about to post a picture. But on the second thought, I don't think the horny goat pix is appropriate here in the cafe.

Market Failure

And this is the hilarious yet tragic example of it: the fiasco of self-proclaimed scientist turned TV celebrity and best-selling author in UK. Here is the lead:

For years, "Dr" Gillian McKeith has used her title to sell TV shows, diet books and herbal sex pills. Now the Advertising Standards Authority has stepped in. Yet the real problem is not what she calls herself, but the mumbo-jumbo she dresses up as scientific fact, says Ben Goldacre.Certainly, if the article is correct, the viewers of her TV shows, buyers of her books, and consumers of her Wild Pink Yam and Fast Formula Horny Goat Weed Complex pills are doomed. Consumers who do not have information as Dr (err, no) Gillian McKeith has (or pretends to have), buy products with no medical value --while in fact efficiency-wise they shouldn't buy those fake products at all.

To prevent that thing happens and to rectify the market efficiency, economics allows various government related authorities to step in --Advertising Standards Authority and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, in this case.

You see, mate. We don't always hate government and loathe regulation.

ps: Following Aco, I was about to post a picture. But on the second thought, I don't think the horny goat pix is appropriate here in the cafe.

Market Failure

Saturday, April 22, 2006

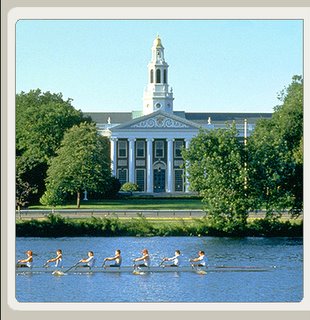

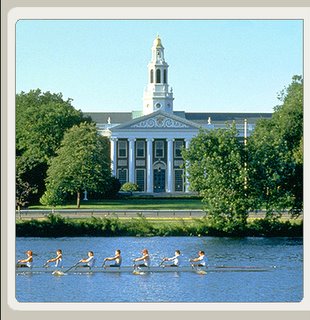

From the Charles RIver

As Aco said, I am mostly away from the blogworld, taking a walk along the Charles River. The river marks the boundary for Boston and Cambridge, as well as the Essex and Middlesex counties of Massachusetts. It's spring time, so the pathway is just too beautiful to miss.

Everytime I walk along the river from my apartment to school, I always stare enviously at the big, luxurious complex of the Harvard Business School (HBS). While the main campus is in the Cambridge side, HBS - and the stadium - is located in the other side. It's a world in its own. We on the other side of the river often call it, sarcastically but enviously, the 'Allston Country Club,' after the neighborhood of Allston.

Everytime I walk along the river from my apartment to school, I always stare enviously at the big, luxurious complex of the Harvard Business School (HBS). While the main campus is in the Cambridge side, HBS - and the stadium - is located in the other side. It's a world in its own. We on the other side of the river often call it, sarcastically but enviously, the 'Allston Country Club,' after the neighborhood of Allston.

My Kennedy School of Government (KSG) campus lies just across the river on the Cambridge side. The other Harvard schools and the main Yard is another 5-10 minute walk. It's also a nice place, but nothing compares to the other side of the river in terms of size and luxury. As we often jokingly said, this is how the public (government) sector compares with the private (business) one.

My Kennedy School of Government (KSG) campus lies just across the river on the Cambridge side. The other Harvard schools and the main Yard is another 5-10 minute walk. It's also a nice place, but nothing compares to the other side of the river in terms of size and luxury. As we often jokingly said, this is how the public (government) sector compares with the private (business) one.

Speaking of private vs. public sector, students of both school run an annual debating contest between them. The usual theme is "which school produces the real leader?" Or, in a more general term - which one is the real agent of change: business or public sector?

As you know, the U.S. had had great political leaders like Jefferson, Franklin, Maddision, Washington, or Lincoln and Kennedy. But the country was also shaped by businessmen and enterpreneurs like Carnegie, Mellon, Rockefeller, and Bill Gates in the modern world. Of course, each side has its dark side. Enron was just an example of business sector corruption. Or the 1930's great depression showed how (financial) market failure can lead to a global disaster. On the other hand, Nixon's watergate provides a high-profile example of public sector corruption. And we can cite so many examples on how government failure caused greater problems than the market failure (what do you think of the 'aid failure,' Prof. Sachs?).

You can read my note on last year's debate here. This year's debate was not that different with the previous one, so the note is still update.

So, which school provides the true agents of change? The thing is, 70% of HBS graduates work in the consulting firm. They don't really become enterpreneurs - the real private sector agents of change. Most of the KSG graduates still work in the 'public' sector (in a broad term), and some of them go. But still a great portion goes into the private sector, competing with the HBS fellows in the same job market. So I guess, in the end, they are even...

Academic life

Everytime I walk along the river from my apartment to school, I always stare enviously at the big, luxurious complex of the Harvard Business School (HBS). While the main campus is in the Cambridge side, HBS - and the stadium - is located in the other side. It's a world in its own. We on the other side of the river often call it, sarcastically but enviously, the 'Allston Country Club,' after the neighborhood of Allston.

Everytime I walk along the river from my apartment to school, I always stare enviously at the big, luxurious complex of the Harvard Business School (HBS). While the main campus is in the Cambridge side, HBS - and the stadium - is located in the other side. It's a world in its own. We on the other side of the river often call it, sarcastically but enviously, the 'Allston Country Club,' after the neighborhood of Allston. My Kennedy School of Government (KSG) campus lies just across the river on the Cambridge side. The other Harvard schools and the main Yard is another 5-10 minute walk. It's also a nice place, but nothing compares to the other side of the river in terms of size and luxury. As we often jokingly said, this is how the public (government) sector compares with the private (business) one.

My Kennedy School of Government (KSG) campus lies just across the river on the Cambridge side. The other Harvard schools and the main Yard is another 5-10 minute walk. It's also a nice place, but nothing compares to the other side of the river in terms of size and luxury. As we often jokingly said, this is how the public (government) sector compares with the private (business) one.Speaking of private vs. public sector, students of both school run an annual debating contest between them. The usual theme is "which school produces the real leader?" Or, in a more general term - which one is the real agent of change: business or public sector?

As you know, the U.S. had had great political leaders like Jefferson, Franklin, Maddision, Washington, or Lincoln and Kennedy. But the country was also shaped by businessmen and enterpreneurs like Carnegie, Mellon, Rockefeller, and Bill Gates in the modern world. Of course, each side has its dark side. Enron was just an example of business sector corruption. Or the 1930's great depression showed how (financial) market failure can lead to a global disaster. On the other hand, Nixon's watergate provides a high-profile example of public sector corruption. And we can cite so many examples on how government failure caused greater problems than the market failure (what do you think of the 'aid failure,' Prof. Sachs?).

You can read my note on last year's debate here. This year's debate was not that different with the previous one, so the note is still update.

So, which school provides the true agents of change? The thing is, 70% of HBS graduates work in the consulting firm. They don't really become enterpreneurs - the real private sector agents of change. Most of the KSG graduates still work in the 'public' sector (in a broad term), and some of them go. But still a great portion goes into the private sector, competing with the HBS fellows in the same job market. So I guess, in the end, they are even...

Academic life

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)